The taxonomy of the Sinningia Alliance can be confusing even for experts. Understanding the taxonomy isn’t necessary for appreciation of the plants, so feel free to skip ahead to the next sections of the article.

Although the family tree of the alliance is well established through the work of Alain Chautems, Mathieu Perret (both from the Geneva Botanical Garden) and others, the nomenclature is in a state of flux and probably will remain so for some time. It is not even certain that the genus name Sinningia will survive.

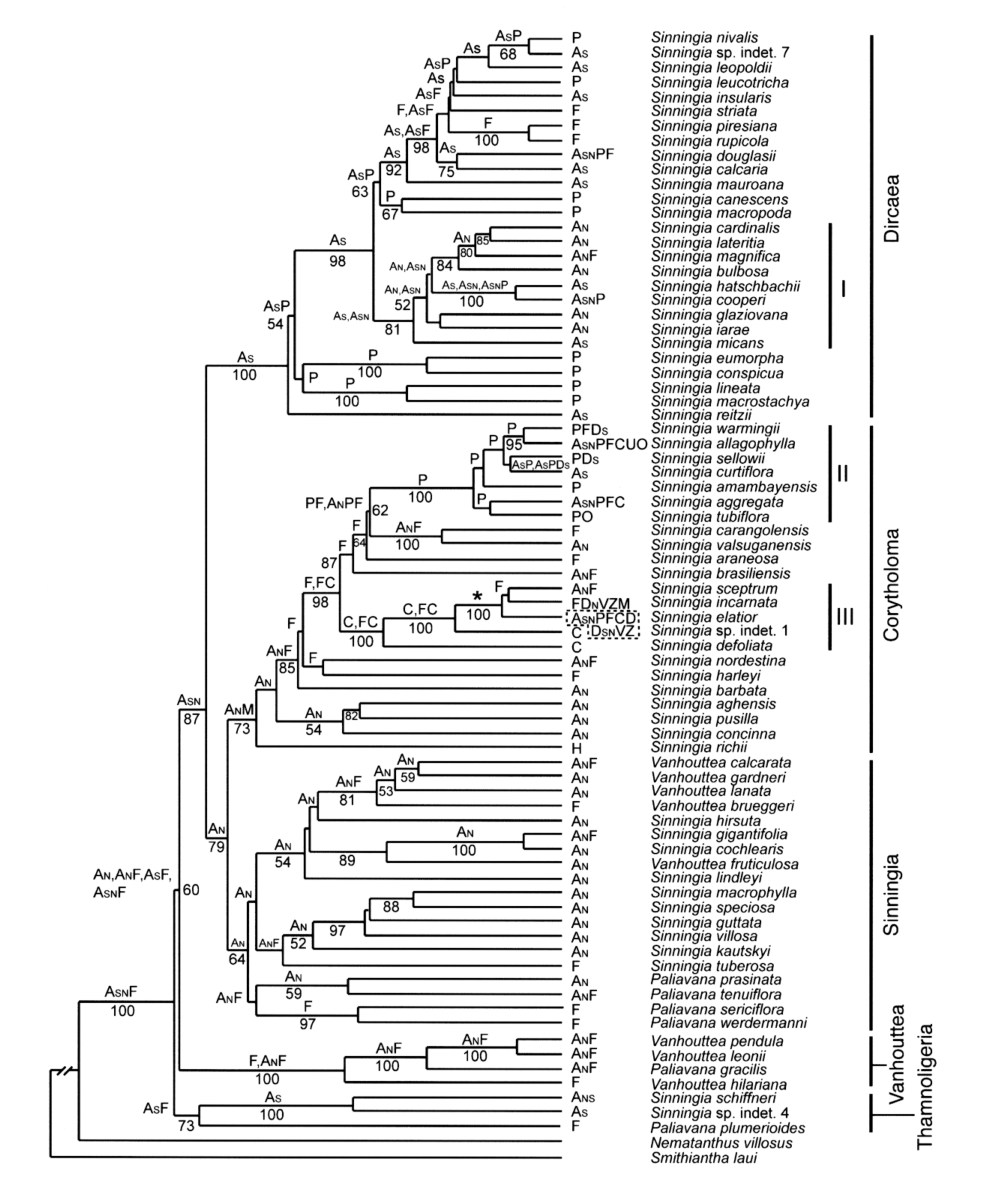

The problem with the nomenclature within the alliance is that recent genetic analyses have shown that the genera Sinningia, Paliavana, and Vanhouttea, as currently defined are not natural groupings. These names are going to have to be disentangled. A variety of solutions are available, including lumping everything together into a single genus or creating new genus boundaries, based on what appear to be valid taxonomic groupings.

These latter are Dircaea, Corytholoma, Sinningia, Vanhouttea and Thamnoligeria, which are covered in detail in the next few pages. Final disposition of the Sinningia Alliance awaits formal publication by some intrepid botanist.

As is apparent, the taxonomic history of the Sinningia Alliance is tortuous and confusing, so an overview of the history may be useful.

A hundred years ago, the concept was to allocate tuberous species with bell-shaped (campanulate) corollas to the genus Sinningia (example: Sinningia speciosa) and tuberous species with tubular flowers to a different genus, Rechsteineria. Part of Hans Wiehler’s pioneering work was to show that corolla shape was adapted to the pollinator and not necessarily the mark of a close genetic relationship. For example within Rechsteineria, R. cardinalis was found to belong to the Dircaea group, while R. allagophylla wound up in the Corytholoma group. They were related, but not more so than either was to Sinningia. It was concluded that Sinningia and Rechsteineria needed to be brought together into a single genus, so one of the two had to be sunk into the other. Because Sinningia was the older name, it prevailed and now contains all the former Rechsteineria species.

The general scheme which created the current situation was to put the tuberous species into the genus Sinningia (now including the former Rechsteineria), and then split the remaining tuberless species into Vanhouttea (red tubular flowers) and Paliavana (white or purple campanulate flowers). The trouble was that flower color and shape are determined by pollinator type and turned out to be much more mutable than expected. This kind of arbitrary sorting (just as in the Sinningia/Rechsteineria case) has not proven valid, in light of the most recent scientific work.

In addition, a number of species were originally described within genera that have not proven valid. Most of these have been merged into Sinningia.

Lietzia, for example, was a genus erected solely for the species L. brasiliensis, again based on corolla shape and features which are most likely the result of pollinator type (in this case, bats). This species falls within the Corytholoma group and has been transferred to Sinningia (as S. brasiliensis).

A number of sinningias were at one time published under the genus name Ligeria, although only one species (now S. gesneriifolia) was published originally under that name. These species have long since been moved to the genus Sinningia, but this extinct genus has left a baleful legacy. At one point a subtribe (a taxonomic level between genus and family) Ligeriinae was erected to house these species, plus the genus Sinningia. When the Sinningia tribe (a category above subtribe) was demoted to subtribe status in 2010, the long-dormant name Ligeriinae sprung its trap! The arcane rules of botanical nomenclature forced the name upon the new Sinningia subtribe, even though there haven’t been any Ligerias for a long time. The name also survives as part of the group name, Thamnoligeria.